Riding Trauma: Fight, Flight, Freeze, & Discharge

What Rabbits Can Teach Us About Recovering From Bad Experiences

by Betsy Crouse, ACAP-EFT

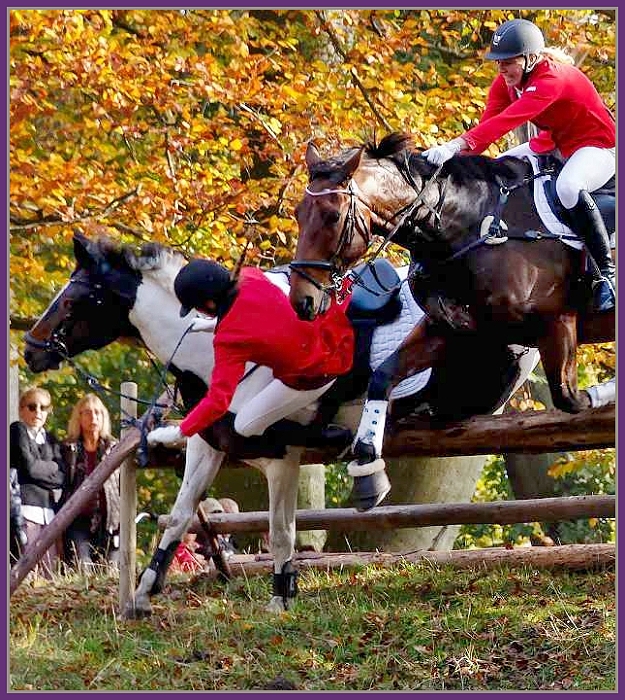

Bucked off, run away with, dumped at a jump – any one of these is bad enough for a rider. But sometimes things get worse. Memory of a bad riding experience can fade quickly, or… it can linger on and on, replaying in the mind, causing fight-or-flight symptoms in the body. It can turn the pleasure of riding into a miserable struggle for inner control.

Bucked off, run away with, dumped at a jump – any one of these is bad enough for a rider. But sometimes things get worse. Memory of a bad riding experience can fade quickly, or… it can linger on and on, replaying in the mind, causing fight-or-flight symptoms in the body. It can turn the pleasure of riding into a miserable struggle for inner control.

When this happens we’re likely to beat ourselves up, thinking we lack the willpower to “just get over it.” We hate the jittery nerves, racing heart, and worse. Why can’t we be braver? We might even hear it from family, peers or coaches: “Come on, buck up!”

In fact, the problem has nothing to do with a lack of willpower, toughness, or bravery. It has to do with the absence of something that small, terrified creatures like rabbits do automatically after each life-or-death encounter in the wild. That something is known as the “discharge response.” (And we can make up for it when it’s missing – more about that later.)

A Lesson From Nature

Trauma experts Dr. Peter Levine and Dr. Robert Scaer pioneered decades of work on the discharge response. Dr. Levine, a psychologist who works with severely traumatized clients, wondered why wild animals, routinely threatened with death by predators, show none of the post-trauma effects so common in humans. His study of this question led to a striking new understanding of why people become traumatized.

Dr. Scaer, a neurologist, had been referring treatment-resistant patients to Dr. Levine. When these patients experienced dramatic improvements Scaer was deeply impressed, and drawn into his own quest to understand. At the heart of what the two men discovered lies the discharge response.

To understand how it works, consider a young rabbit grazing in your backyard. You open the back door and your dog slips out, spots the rabbit, and launches forward. The rabbit explodes into action. To help her reach safety, her brain/body system unleashes a cascade of fight-flight inner events, accompanied by a massive release of biochemicals.

To understand how it works, consider a young rabbit grazing in your backyard. You open the back door and your dog slips out, spots the rabbit, and launches forward. The rabbit explodes into action. To help her reach safety, her brain/body system unleashes a cascade of fight-flight inner events, accompanied by a massive release of biochemicals.

In this drastically altered state the rabbit has access to a huge amount of energy which propels her toward cover at lightning speed. As the rabbit reaches her burrow, the dog lunges hard and his teeth close on soft fur. But he is, as they say, a hair short, and although the rabbit feels a sharp tug, she hurtles into darkness and safety.

The Freeze and the Discharge

Plunging to the bottom of her den, the rabbit collapses. Totally inert, she seems dead. What happens next is described by Dr. Levine in his book, Waking the Tiger. Soon the rabbit starts to tremble, then shake all over. She draws a deep breath, and… comes back to life. In a short while she is grooming herself, fully restored.

Her collapse is called the “freeze response.” It occurs when a dire situation (such as a rider losing control of a horse) seems to become hopeless. It’s triggered when fight-or-flight has failed and “doom” seems unavoidable. In our story, the yank on the rabbit’s fur caused the freeze – in that instant her body “thought” death was imminent.

In the freeze state pain does not register, so it’s a mercy for prey animals who are caught and killed. But it also creates a chance for survival, causing even an injured animal to lie quietly. If the predator’s attention then wanders (like a fox-mom who turns to call her kits to dinner), the inert prey animal may quite literally shake “death” off and dash to freedom.

One other note about the freeze: depending on the severity of the trauma, its intensity ranges widely, from mild shock to the full-blown immobility seen in the rabbit. Humans rarely collapse, but experience lesser degrees of the freeze state on a regular basis.

The rabbit’s shaking happens as the discharge response takes place. In his book 8 Keys to Brain-Body Balance, Dr. Scaer details how this vigorous movement dissipates the avalanche of survival-biochemicals pumped into the body by the fight-flight response. During this discharge, the brain processes the experience, and the body releases and resolves the associated physical/emotional distress.

So How Does All This Relate to Riding?

Imagine your horse runs off with you on a trail ride, bolts across the road in front of a truck, and throws you into a ditch. Depending on your level of experience, you may fight to regain control; you’ll certainly fight to stay on the horse. And at some point, as your effort fails, your system will trigger the freeze to protect you from anticipated harm.

When things like this happen to us, why don’t we emerge free of after-effects, like the rabbit did? Why, even if we’re ok, are we then likely to avoid trail rides, crossing roads on horseback, or riding that particular horse? Why will doing any of these things likely cause us mild to severe distress, distress that may linger on and on, even becoming permanent?

Levine and Scaer find the answer in something uniquely human: we experience all this post-traumatic stress because we don’t allow the discharge response to happen – we’re taught to not let our body/mind system “complete” a threatening event in the way it’s designed to do.

What do riders hear on the heels of their first fall? “Don’t let it get you down. You can’t give in to your fear – get right back on your horse!” The speaker means well, but the unintended result is that they interrupt the discharge response, and teach us to be critical of natural and important sensations and feelings. We don’t like the sensation of trembling and shaking, or the feeling of fear, and we learn to regard them as signs of weakness. We then do our best to block these sensations and feelings as quickly as we can whenever they occur.

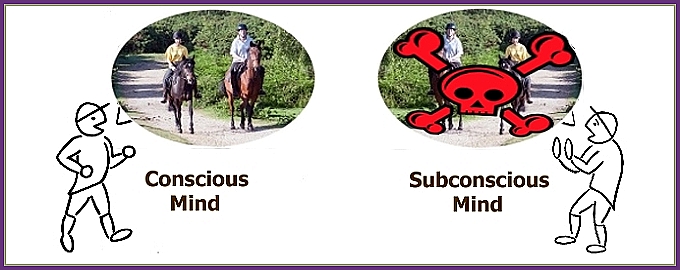

And this is the cause of the negative after-effects. As Scaer describes in 8 Keys to Brain-Body Balance, there is a process in the discharge during which the brain “relegates [the event] to the past as a survival learning experience.” Without the discharge, he explains, the experience is stored “as if the threat still exists, and thereafter, any cues linked in any way to the experience of the unresolved threat will trigger the fight-flight response…” (underscore added, p.99)

Dr. Scaer’s words answer all the questions about our future negative reaction to circumstances related to our road accident. Regardless of our desires and goals, our subconscious mind and energy system, completely beyond our conscious control, keeps getting triggered by “any cues linked in any way” to that accident.

Whether we’ll overcome being traumatized on our own depends on many things: the intensity of the threat, whether we were injured (if yes, how badly), how helpless we felt, whether there were subsequent, related traumas, and, of course, whether the discharge response was able to complete itself. The milder the trauma, the more likely we’ll work it out naturally.

It’s easy to know if and when we have – we won’t experience any sign of fight-flight symptoms in similar circumstances. No jittery nerves, increased heart-rate, sweaty palms, scattered focus, or worse. For riders, this may also involve consideration of things like further training for a green horse, so noisy traffic won’t be a problem.

But one thing Levine and Scaer found is certain: we can help our system release the undischarged after-effects of even major trauma, and even if it happened years ago.

Their finding blends with and complements the work done by another handful of pioneers who, in the same timeframe, gave birth to the new and growing field of “energy psychology.” Out of this collective work have come new techniques for releasing trauma that mimic the results of the discharge response. The most well-known of these is an acupressure-related technique called EFT, for Emotional Freedom Techniques (aka “tapping”).

Part 2 of this article, “How Come Bronc Riders Don’t Get Traumatized?”, will look further into why some riding mishaps produce lingering negative effects while others don’t and why for some riders but not others; will explain how and why a problem can develop over time and “show up out of the blue;” and introduce Emotional Freedom Techniques, or EFT, a powerful but gentle step-by-step process which can give riders what Nature intended – the ability to release negative residue from trauma, whether large or small, recent or long past.

Like the rabbit, we can emerge from a riding accident steady and strong, and return to riding with joy and confidence.