How Come Bronc Riders Don’t Get Traumatized?

A Deeper Understanding of the Freeze Response & the Fight-Flight “Tape Loop”

by Betsy Crouse, ACAP-EFT

What happened the last time you fell off? Did you dust off and remount, little worse for wear? Feel some mild worry for a while? Or did the fall leave you with lasting tension and anxiety that is now sapping the joy from your riding?

What happened the last time you fell off? Did you dust off and remount, little worse for wear? Feel some mild worry for a while? Or did the fall leave you with lasting tension and anxiety that is now sapping the joy from your riding?

Part 1 of this article focused on the three major components of the brain-body response to danger: the well-known fight/flight, the lesser-known freeze, and the almost unknown discharge. It explained that the discharge neutralizes the after-effects of a threatening experience, and described how it functions superbly for wild animals like the rabbit in the story. Finally, Part 1 looked briefly at how and why we humans often block the discharge after we encounter danger, and how, instead of recovering easily, we can then get stuck in a recurring tape-loop of fight-flight symptoms

Here in Part 2, we’ll look more deeply into that tape-loop trap to find out why it happens sometimes, but not others, and why a lingering problem can seem to come out of the blue, even for a lifelong rider. Here we’ll also get an introduction to the acupressure-related process called Emotional Freedom Techniques, known as EFT, or Tapping.

tHE dIFFERENT fACES OF fALLING oFF

It’s obvious that a fall itself doesn’t always cause a problem. In fact, rodeo bronc riders make a living getting thrown from the horses they ride. Many of those falls are spectacular; many result in injury. But the riders are back in the chute as soon as possible. How can that be? Why aren’t they paralyzed with anxiety?

It might seem that those folks are just plain braver than the rest of us. But that’s not it. The bronc rider is in a dangerous situation and his body unleashes the same fight-flight rush of adrenaline and other biochemicals that we’d feel in his place. But here is the difference – he’s in a situation he has deliberately chosen and very consciously prepared for. Because of that, even as he parts company with his mount his system doesn’t trigger the freeze response. And that is key.

The freeze is a survival tactic, a kind of shut-off valve, that kicks in when fight-flight options fail and we feel helpless to help ourselves in the face of perceived harm. (Among other things, the freeze is designed to protect us from pain.) Our bronc rider doesn’t hit that point – he’s in “fight” mode – processing what’s happening and responding to it instant by instant, all the way through to the finish when he gets up and walks away. (Note: not to say that he couldn’t ever experience the freeze during a ride/fall, depending on what happens.)

In contrast, compare that to a novice rider on a horse that starts bucking. She may get thrown within seconds, but many brain-body processes will take place in the meantime. Her fight-flight adrenaline response will kick in, but since she’s unable to flee and lacks the riding skill to fight for balance or control, her system will trigger the freeze to protect her from what it perceives as certain harm. At that point she’ll stop consciously processing what’s happening, but other parts of her brain and her body will record all of it.

In contrast, compare that to a novice rider on a horse that starts bucking. She may get thrown within seconds, but many brain-body processes will take place in the meantime. Her fight-flight adrenaline response will kick in, but since she’s unable to flee and lacks the riding skill to fight for balance or control, her system will trigger the freeze to protect her from what it perceives as certain harm. At that point she’ll stop consciously processing what’s happening, but other parts of her brain and her body will record all of it.

After the fall she’ll come out of the freeze, and a well-meaning friend or instructor, or the rider herself, will probably encourage her (especially if she’s not seriously hurt) to “brush it off.” This usually means putting on a brave face and trying to squash any feelings of helplessness, fear, anger, embarrassment, or inadequacy, as well as the sensations associated with them. That is where we humans part company with the wild rabbit from Part 1, and where our problems begin.

A Real-Life Time Warp

Once the freeze has been triggered and our conscious participation has shut down, our brain-body needs the discharge to “finish processing the event.” But when we deliberately try to control or shut off the feelings and sensations associated with the event, we block the discharge from taking place. And then a strange thing happens.

As described by trauma expert Robert Scaer, MD, in Chapter Six of 8 Keys to Brain-Body Balance, we now undergo a “corruption of memory,” and the details of the event get stored in the brain as a current event, rather than a past one. From that point forward, unless and until the processing is completed, our inner alarm system can get triggered by any of the cues (sights, sounds, smells, sensations, thoughts, emotions) linked to the original event, and then react as if the original situation, with all its sense of impending danger, were currently happening. And so the internal tape-loop is born.

Once this tape-loop gets rolling, it becomes a source of ongoing frustration and discouragement. Willpower is helpless in the face of it. The alarm system that triggers the tape-loop reaction is “so fast and powerful that, when activated, it overrides all other brain activity,” (Scaer, 8 Keys to Brain-Body Balance, p.55). Locked in that state and unable to process information, a rider cannot respond to a new problem situation in a productive way. Even if he/she “knows what to do,” in that moment it is impossible to do it.

As this chain of events repeats itself over time, with environmental cues triggering a fight/flight response, dread of the symptoms themselves, along with the inevitable self-criticism, adds to the problem and begins producing a network of inter-related triggers.

It’s important to add a few things here. I used the novice rider for contrast with the bronc rider, but the freeze response can and does get triggered in experienced riders, too. Experience can enable a rider to avoid the freeze state because he or she has more “fight/flight tools and options” than a beginner, but once it kicks in, the thinking part of the brain shuts down for experts just as it does for beginners. Even the most experienced riders can encounter a situation that overwhelms their ability to retain or regain control, and if the freeze state is activated and not followed by the discharge, an experienced rider is left with lingering triggers and symptoms just as a beginner is. This can be especially difficult for seasoned riders or professionals, who may judge themselves very harshly for not “being able to snap out of it.”

It’s also possible that the recurring symptoms we’re talking about can seem to show up out of nowhere, perhaps following a relatively minor incident that doesn’t seem like it could possibly be responsible for a persistent problem. This can happen when a series of freeze-inducing events, taking place over time, produces a gradually accumulating list of cue-triggers, until eventually even very familiar horse-related activity can function as a danger alert to the body/brain system. Extreme frustration follows, as things a rider may have been doing for years without a problem now produce racing heart and other symptoms.

The final situation to mention is a single incident involving serious injury, hospital treatment, extensive rehab, and/or other complications of the fall itself. In such cases, just that one event can generate a list of cue-triggers so large that symptoms may also subsequently be linked to and get triggered during even mundane riding activity.

In its full-blown state, the familiar post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), this negative tape-loop is what ruins the lives of combat veterans and other victims of severe trauma. In our lesser version, it ruins a rider’s ability to enjoy an activity that used to be one of the best things in life.

Introducing EFT, aka “Tapping”

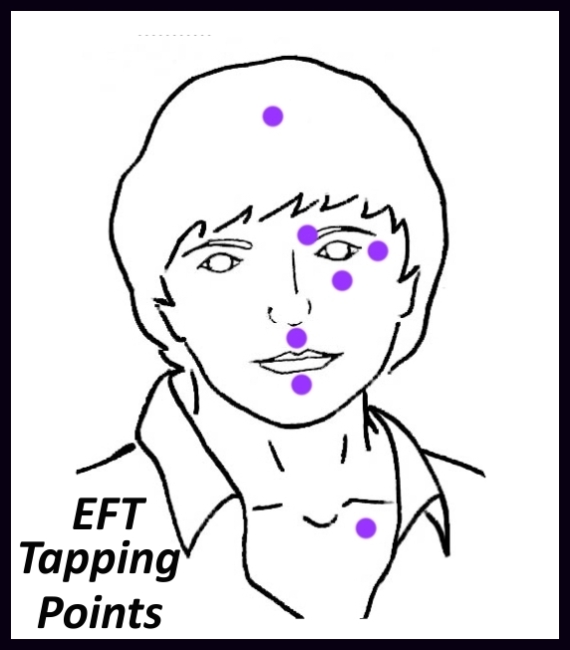

Enter a strange looking process called EFT, the acronym for Emotional Freedom Techniques (also known as Tapping). EFT was founded in the early 1990s by Stanford-trained engineer Gary Craig, based on the work of psychotherapist Roger Callahan and others. It is the most well-known of a handful of therapeutic techniques in the developing field of “energy psychology.” The basic process involves tapping on a series of acupressure points with the fingertips, while holding a specific mental/emotional focus.

Enter a strange looking process called EFT, the acronym for Emotional Freedom Techniques (also known as Tapping). EFT was founded in the early 1990s by Stanford-trained engineer Gary Craig, based on the work of psychotherapist Roger Callahan and others. It is the most well-known of a handful of therapeutic techniques in the developing field of “energy psychology.” The basic process involves tapping on a series of acupressure points with the fingertips, while holding a specific mental/emotional focus.

During an EFT session for an event like a riding fall, the various aspects of the event are addressed piece-by-piece in a systematic way, with care taken to minimize the associated distress. In this way EFT is very unlike many approaches to reducing lingering fight/flight symptoms, which often try to override or replace uncomfortable feelings and sensations using positive suggestions, or by providing something else to focus on.

The exact biophysical reasons that successful EFT nullifies the negative after-effects of a difficult event are not yet completely understood, but it mimics the effect of the discharge response, and a growing body of research supports its efficacy. Thought Field Therapy (TFT), the modality from which EFT was developed, is now listed in the National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices, and training in EFT is accepted for continuing education credits by the American Psychology Association.

Happy Rabbit, Happy Rider

The rabbit in Part 1 of this article narrowly escaped from the dog with her life, but was calmly grooming herself a short while later. The discharge response enabled her to release all the stress and distress of her brush with death. At the same time, she was able to retain useful information from the event, such as having learned that the sound of the backdoor latch means she should “pay attention, now!” She’ll be free to make use of that information in a state of relaxed alertness the next time she is out grazing in the yard.

With the help of EFT or one of the other energy psychology techniques, a rider who’s been trapped in the misery of a fight-flight tape-loop from a riding mishap (or series of them) can experience relief from those symptoms. And like the rabbit, that rider can retain useful information from the experience. For instance, it’s good to know the kinds of things that make one’s horse spook, good to know which farm on a trail ride has a dog that doesn’t like visitors, good to know (until you can get the needed training done) if your horse is afraid to go through gates with you mounted, and so on. And it’s much, much better to be aware of those things in their relevant situations without those alarm bells clanging all through your system!.

In the third part of this series, EFT: A Different Approach to Restoring Riding Confidence, you’ll learn more about EFT and follow the story of Amy Thompson, a lifelong rider who, after a bad fall, was stuck for nearly a year in the misery of recurring symptoms and joyless riding.

Then she discovered EFT and reclaimed her riding joy.